It’s a New Mexico Thing

Let’s face it: New Mexicans are a proud bunch. Whether it’s our quintessential crops, stunning views or famous former residents, we all seem to brag in unison about things that remind the rest of the country there’s actually a state between Arizona and Texas.

But, like it or not, we’re also a cynical lot.

When it comes to building on the excitement of, say, a professional soccer team — both figuratively and literally — there’s a near unanimous pumping of the brakes. That’s kind of what’s happening now as New Mexico United is making moves to build itself a stadium of its own.

New Mexico’s popular soccer team won off the field in November when the Albuquerque City Council greenlit a lease agreement with United that allows the team to use a chunk of land at the city-owned Balloon Fiesta Park. The city will use about $13 million of state capital outlay money to improve infrastructure and get the site ready, and the soccer club will foot the $30 million bill to build a stadium. United will pay about $30,000 each year in rent and fork over 10% of parking revenue. But it wasn’t an easy sell for some councilors and many city residents.

Maybe it’s the list of now-defunct sports teams, or even a popular indie band that blew town for the Pacific Northwest, that fuels the, “This is why we can’t have nice things” feeling that adds a few ice cubes to our warm glass of New Mexico pride.

Sure, many of us are excited for a new stadium, and sure, the slice of public money going towards infrastructure improvements comes from tax dollars that are essentially already spent. But many still can’t shake the feeling we’re going to get burned — again.

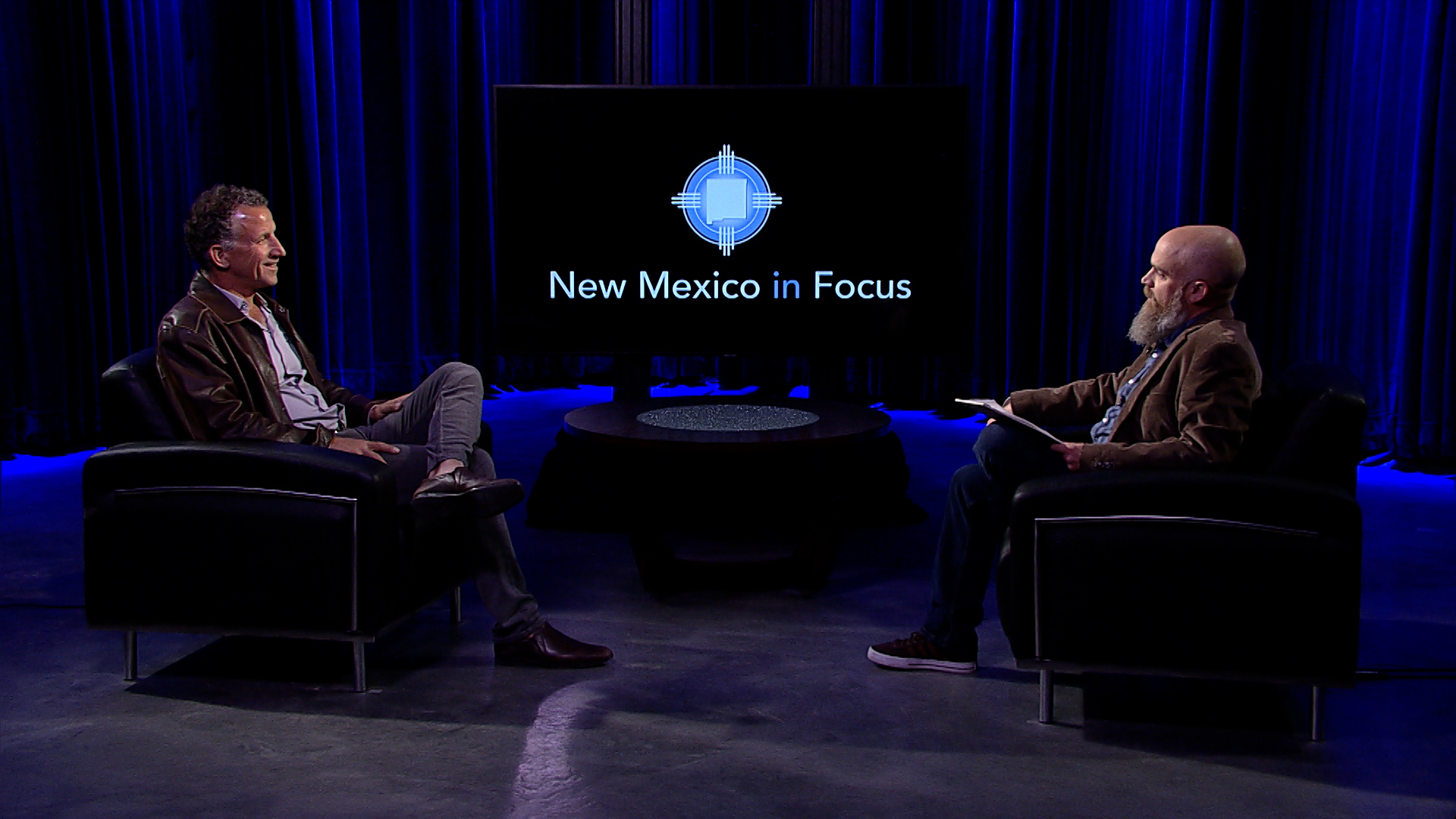

That’s partly why I wanted to interview New Mexico United CEO and majority owner Peter Trevisani: to hear directly from him some specifics of the new stadium his organization is funding. I felt like it was also important — and more than fair — to ask how things have changed since voters in 2021 rejected the idea of a publicly funded stadium and whether voters should have had a say this time around.

New Mexico United, along with at least one independent group, threw a ton of resources into the mix in an attempt to sway voters two years ago. Trevisani says he had the best night’s sleep in his memory after 65% of voters shot down the idea of using general obligation bonds to build a stadium, mostly because he thought, “OK, that’s behind us.”

From there, he says, the organization knew the only other option was to self-fund a stadium, which brings us to the present day. But in Round 2, approving the new stadium became a real example of representative democracy: Instead of letting voters weigh in directly, the decision rested with the Albuquerque City Council.

Trevisani bristled a bit at my questions about whether voters should have been allowed to consider some ballot language this year, arguing that people wouldn’t normally get to vote on most other privately funded projects such as new apartment complexes.

“There’s no end-around because the city isn’t spending a dime,” he told me.

Another difference in 2023: The dark cloud of New Mexico possibly losing the team. The United Soccer League made no secret about plans to drop teams without a devoted home field. The USL showed it wasn’t messing around when it yanked the franchise rights of San Diego Loyal in August after that club failed to secure its own stadium. Curiously, though, New Mexico United never publicly presented the possibility of folding as a reason to move forward with a lease agreement with the city.

Trevisani told me he purposely avoided bringing that up because he didn’t think threatening the city would move the needle as much as highlighting the positive elements of having a professional team.

With the bureaucratic approval process out of the way and a shiny new stadium on the horizon, Trevisani hopes to have a new stadium by or before the team’s current sub-lease at Isotopes Park expires in 2026. But he also wants to make sure his organization takes concerns from residents — including those who live close to the balloon park — into account and not “take any shortcuts.”

– Andy Lyman Editor, The Paper.

This story was produced in collaboration with The Paper., a NMPBS partner.

-

Poetry As a Way To ‘Build Empathy’

12.1.23 – For New Mexico Poet Laureate Lauren Camp, poetry is a way to “build empathy.” In conversation with Our Land…

-

State Rep., Teachers Union President on PED Calendar Change Proposal

12.1.23 – Albuquerque Teachers Federation President Ellen Bernstein and state Rep. Joy Garratt, an Albuquerque Democrat and former teacher, join Senior…

-

Santa Fe Music Teacher Questions PED Calendar Change Proposal

12.1.23 – The state Public Education Department wants to expand school calendars, increasing the number of instructional days required for students…

-

NM United’s Peter Trevisani on New Stadium

12.1.23 – This week on New Mexico in Focus, New Mexico United CEO and President Peter Trevisani stops by our studio…