Our Land: A Decent Winter Becomes a Lousy Spring on the Rio Grande

Two years ago, New Mexico’s largest river dried in April, right when the Rio Grande would normally churn with muddy spring snowmelt.

It was a bad situation—harmful to endangered species and the ecosystem, worrisome for farmers who draw water from the river to irrigate their crops and orchards, and stressful for water managers.

But it wasn’t unexpected.

The previous winter’s snowpack was abysmally low compared with the long-term average. And forecasters knew that what little runoff might sluice down out of the mountains would be sucked up by dusty soils and parched forests before trickling very far downstream.

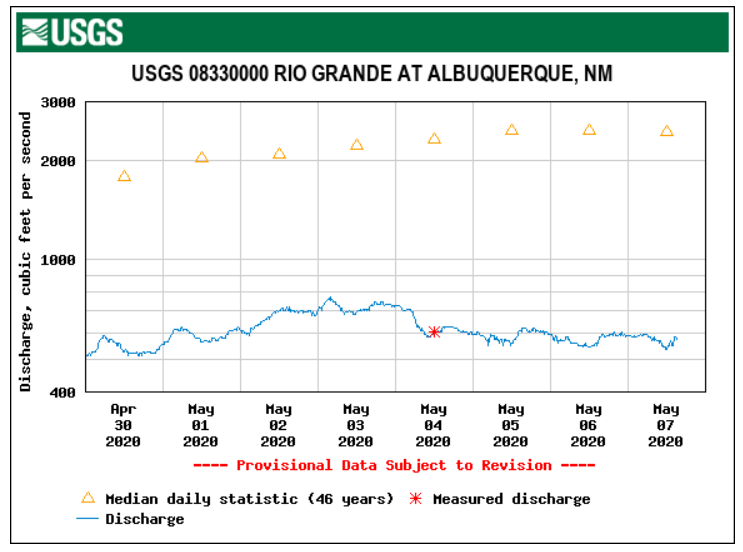

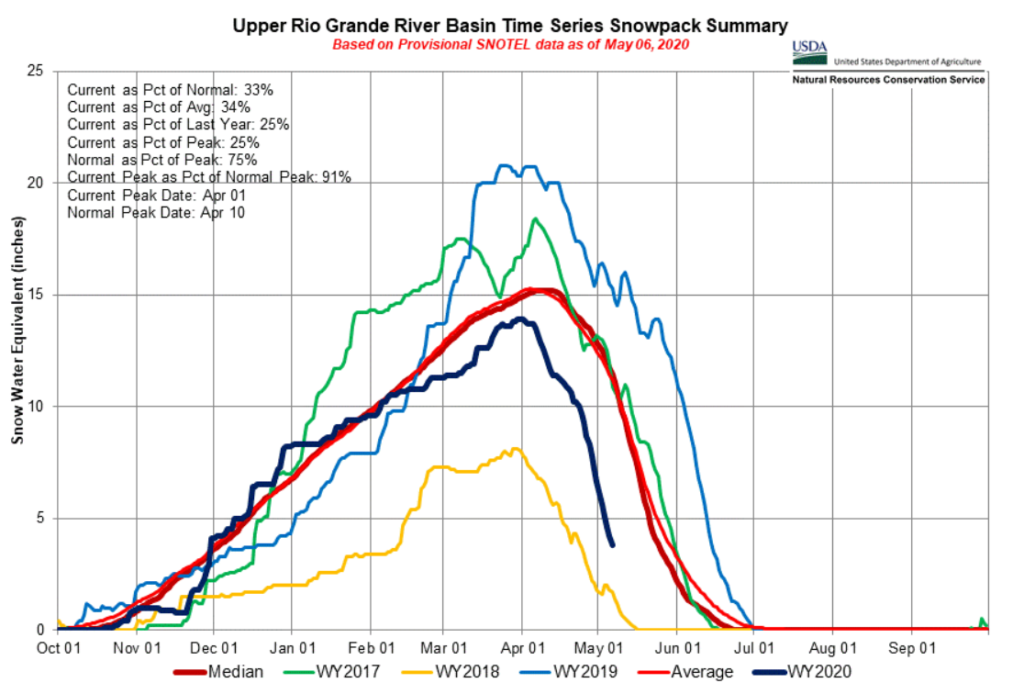

This spring, the Rio Grande through Albuquerque is running at about 20 percent of its historic average—even though snowpack in the watershed was close to average last fall and into February. Conditions won’t get much better: Peak snowmelt occurred last week, according to the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation.

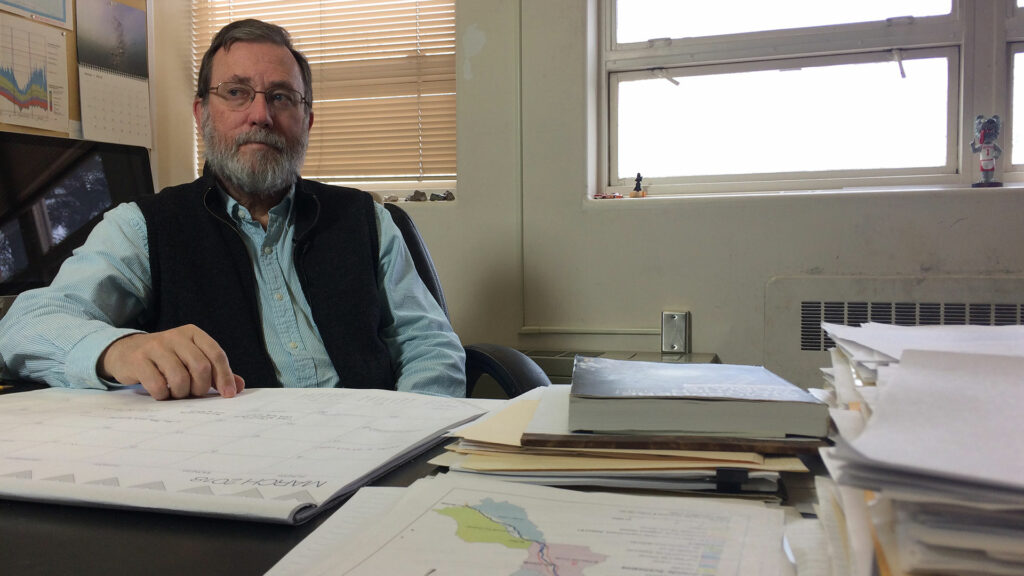

“This year was more along the lines of what I anticipate for the future, to happen more often,” says David Gutzler, professor of Earth and Planetary Sciences at the University of New Mexico. Gutzler has been studying climate change in the southwestern United States for decades.

Increasingly warm conditions play out in predictable ways in the arid Southwest. That includes having less water in rivers, even when the region isn’t necessarily mired in drought, experiencing a deficit in snowpack or rainfall.

“You get snow in the winter when it’s really cold, but then things get warm and dry—which is the long-term outlook for springtime in the Southwest—and the snow just melts away faster than our historical statistics would suggest,” Gutzler says of this year’s conditions. “This is more like a global warming-style of a low streamflow year, as opposed to a drought year [like 2018] that started off bad and stayed warm, and was just bad for the whole winter.”

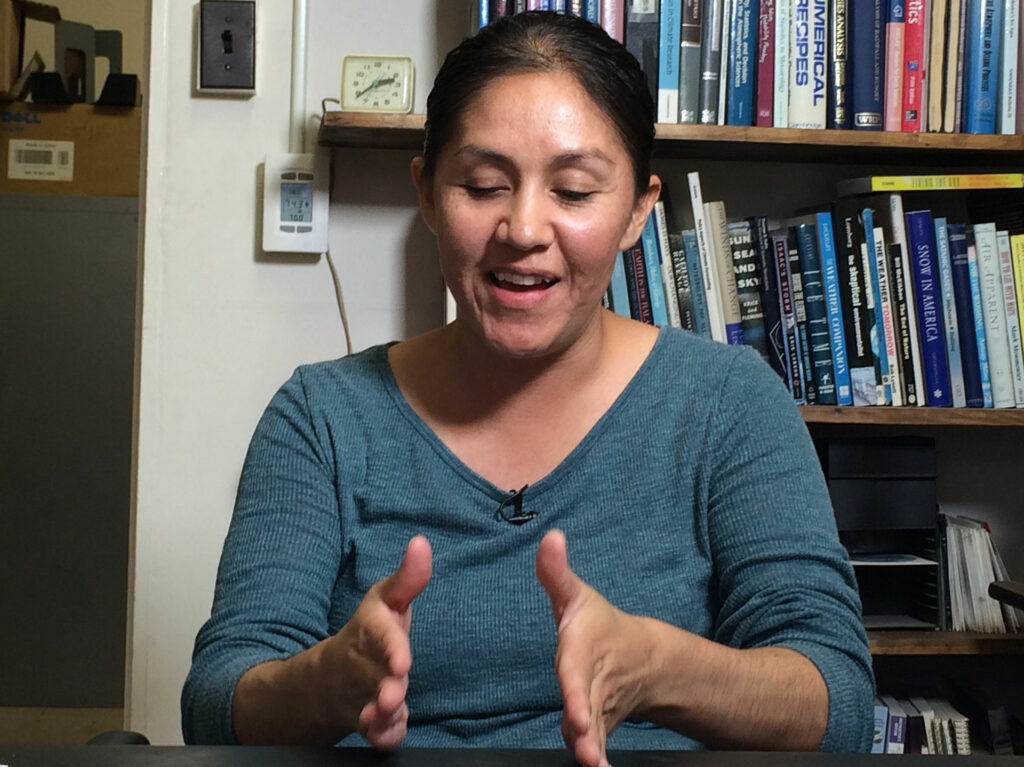

Two years ago, then-UNM graduate student Shaleene Chavarria published her research with Gutzler about declining snowmelt and streamflows in the Rio Grande. In that peer-reviewed study, she looked at annual and monthly changes in climate variables and streamflow volume in the headwaters of the Rio Grande in Colorado between 1958 and 2015. She found that flows are declining in March, April, and May.

Chavarria, a hydrologist, saw something else in the records: Snowpack in the Rio Grande watershed is decreasing. And it’s melting earlier.

That’s definitely playing out again this year.

Looking at the data, Chavarria notes that in 2018 and 2020, snowpack melted out about a month earlier than it normally did in the past. “This is something we address in the paper, and I think it’s interesting and scary to see it happening,” she wrote in an email to NMPBS.

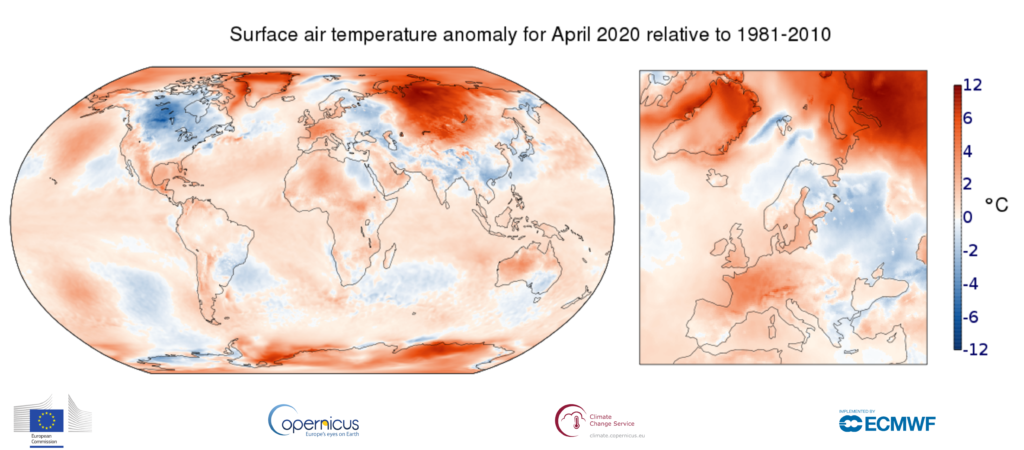

Just since the 1970s, average temperatures in New Mexico have increased by more than two degrees Farhenheit. That warming trend is even more rapid than what’s happening globally. And conditions just keep getting warmer.

Globally, April 2020 was the warmest April on record, according to the European Union’s Copernicus Climate Change Service. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration forecasts 2020 to be one of the five warmest years on record—and there’s a 75 percent chance it will be the warmest year since scientists began tracking global temperatures in the late 1880s.

As temperatures steadily increase, there will still be wet and dry years. Drought is a normal occurrence in the arid Southwest. But research shows that human-induced warming exacerbates droughts—and is pushing them toward the extreme.

Since 2000, the southwestern United States and northern Mexico have experienced longer and longer stretches of dry years. And a new study based on 1,200 years of tree-ring data, as well as climate models, shows that it’s likely that the region is currently experiencing a “megadrought.” According to the peer-reviewed study published in Science, the period from 2000 to 2018 was the driest such span since the late 16th century. That’s about the time when the Chamuscado and Rodríguez Expedition became the first Europeans to cross the Rio Grande near El Paso. The research also shows this is the second driest stretch since 800 CE.

Rising temperatures are increasing both the pace and severity of this current drought, according to the study—and the authors add, “this appears to be just the beginning of a more extreme trend toward megadrought as global warming continues.”

The changes in the timing of spring runoff and in the amount of water flowing within the banks of the Rio Grande affect farmers and cities. They also affect the river’s ecosystem—including the cottonwood bosque—and the species that depend upon its waters and cycles.

Already, according to Carolyn Donnelly with the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, the water management agency has released about 4,000 acre feet of water from upstream reservoirs to prevent riverbed drying—and it plans to release supplemental water again within the week.

When the Natural Resources Conservation Service released its final May streamflow this week, the numbers were “pretty grim,” says Reclamation spokesperson Mary Carlson.

“In March, we were looking at a runoff that was near average. But that just didn’t materialize,” Carlson says. “We will continue to coordinate closely with our water operations partners to ensure that every drop of the supply that we do have will be used in the most beneficial way.”

She adds that New Mexico will likely end up under Article VII restrictions by the middle of June.

Under that provision of the Rio Grande Compact of 1938, New Mexico is only allowed to store water in upstream reservoirs when levels in Elephant Butte Reservoir are above a certain threshold. With little water flowing into that reservoir this year, the state won’t be able to store waters upstream—and Elephant Butte’s levels will keep dropping, too.

The bureau anticipates Elephant Butte’s levels will drop close to its 2018 historic lows, when the reservoir was at just three percent of capacity. (The reservoir, which was built to hold two million acre feet of water, is about 25 percent full this week. Water stored there is allocated to farmers in southern New Mexico and Texas)

Reclamation also anticipates that the Middle Rio Grande will dry within the next month, beginning within Bosque del Apache National Wildlife Refuge in San Antonio.

For decades, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, along with federal, state, tribal, and local partners, has tried to keep the endangered Rio Grande silvery minnow from going extinct. The two-inch long fish was once one of the river’s most abundant. But by the 1990s, its population had plummeted, earning it the dubious distinction of requiring federal protection under the Endangered Species Act. Some of those efforts include releasing water to keep the river flowing longer, and also working with the Middle Rio Grande Conservancy District to release water “spikes” when the minnows are spawning.

When the Middle Rio Grande does dry, as it has many summers since the 1990s, biologists end up in the riverbed, trying to salvage what live minnows they can find. They scoop the fish from pools and puddles, then transport them to sections of the river where flows are high enough to possibly sustain the tiny fish.

Fish and Wildlife Service biologist Thomas Archdeacon anticipates the river will dry around Memorial Day. When that starts happening, biologists will slog through the muddy—and then sandy—riverbed, seeking out the endangered fish.

Conditions look bad this year, he says.

“They are spawning now and through the next couple of weeks, but if the river dries shortly after, what few larval fish are out there won’t survive,” he says, adding that they can’t rescue larval fish.

Given public health orders in the state of New Mexico and the need for social distancing to slow the spread of the novel coronavirus, Fish and Wildlife is having to plan for another “new normal.” In addition to grappling with changes wrought by warmer conditions, they’re also working on a plan for salvage operations under COVID-19.

“If we make it to June without drying, we’ll probably just be using [personal protective equipment,]” Archdeacon says. “If it’s before June, I’m not sure; we may not be able to do anything.”

[…] the spring, I talked to him about snowpack. At the time, Rio Grande was running about 20% of its historic average through Albuquerque. Those […]

[…] the spring, I talked to him about snowpack. At the time, Rio Grande was running about 20% of its historic average through Albuquerque. Those […]