“Memories that do not heal”: the legacy of uranium mining at Laguna Pueblo

Following passage of the Radiation and Exposure and Compensation Act expansion, which includes post-1971 miners for the first time, Searchlight spoke with three tribal members whose lives were changed forever by a toxic industry.

by Aviva Nathan, Searchlight New Mexico

This story was originally published at Searchlight New Mexico, a NMPBS partner.

On July 25, I drove to the Pueblo of Laguna to speak with Loretta Anderson, Millie Chino and Vincent Rodriguez, steering members of an advocacy group called the Southwest Uranium Miners Coalition Post-71. Anderson co-founded the organization in 2014 to fight for the expansion of paid benefits — to uranium workers who entered the industry after 1971 — under the Radiation Exposure and Compensation Act (RECA), the 1990 law created to provide financial support to people exposed to radiation from atomic weapons testing as well as the milling, mining and transporting of uranium.

At Laguna, the mines deformed the hills into tiered sites of extraction that are still gray from the uranium. Infrastructure that was built for the mining still remains, now in a state of disrepair. In the wake of mining, what was once a hill collapsed into a contaminated green pond that smells like methane. (The mine in question, called Jackpile Mine, was the largest open-pit uranium mine in the world and operated both underground and open-pit areas.) Anderson’s late husband, Roy Cheresposy, was a miner. Chino lost her husband, James, another miner, in 2023. Vincent Rodriguez was also a miner.

Our conversation took place while we drove around various sites on pueblo land that were affected by mining that happened here between 1953 and 1982. It followed the recent RECA expansion that’s part of President Trump’s One Big Beautiful Bill Act, passed on July 4. This legislation, for the first time, will compensate post-1971 uranium workers, offering a one-time payment of $100,000 to New Mexico workers who meet certain criteria related to exposure and health consequences. Compensation will be overseen by the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ); the agency has yet to release the new RECA application forms.

The urgent desire of downwinders and uranium workers to be compensated after decades of waiting has been seized upon by lawyers, home health care companies and other third parties that hope to get a slice of the pie for themselves. Already, there has been a cacophony of misinformation and rumors of unlawful solicitation. (For details on how the application process should work, see our sidebar about frequently asked questions.) Right now, it’s difficult to estimate how much will be paid in expanded compensation. Since Reca was first passed, more than $2.7 billion has been awarded.

While potential applicants are in limbo, the physical source of harm remains unattended. The Jackpile Mine, which was declared a Superfund site in 2013, is vacant, but it’s still exposed and quietly lethal. Meanwhile, members of the steering committee have expressed concern that uranium mining could begin again shortly, given the Trump administration’s eagerness to expand uranium mining, which includes efforts to fast-track the opening of mines in New Mexico. Susan Gordon, a coordinator with the Multicultural Alliance for a Safe Environment, adds that further steps are required of companies before they can start mining again in this state.

Land and memory converged as Anderson, Chino and Rodriguez spoke about the history and intimate impact of uranium mining in Laguna Pueblo. The following transcript is edited for clarity and length.

As I drove onto Laguna land, which sits around 50 miles west of Albuquerque, Anderson drove ahead of me and contextualized the landscape over the phone. I’ve added Chino’s comments from a trip on the same roads a few hours later.

Millie Chino: They used to have sheep camps along these hills, years ago before the mining started. But once it started, they couldn’t herd anymore, because of the blasting and all the production going on. Many of our people were farmers and sheepherders and cattle workers.

Lorretta Anderson: There was no acknowledgement of the harm being done by the mines. That’s the terrible part. If you look up at those hills, you can see where the gray clay is. That gray color is uranium.

That was where the mines were. Part of it, anyway. They did do a reclamation at one time, but they only put on a thin layer of dirt. They didn’t clean it up. That dirt all has to have blown away already. The people who did the reclamation are sick. They didn’t have any protective gear.

Chino: On your left, you’ll see the housing area where the supervisors of the mines and their children and families lived. We’ve been told they’re all deceased. Even their children, they died of cancers. My mom worked there as a housekeeper for one of the big shots. Both my parents passed away from radiation diseases.

Anderson: On the right, you can see the arroyo. Now it’s highly contaminated. It’s seeping down the Rio San Jose. Uranium contaminated our Mesita Dam. And there’s a little lake here that’s highly contaminated. That is a hot spot. They don’t know what to do with it. If you stop here, you will see that the horses, cattle and all the animals drink off that area where it’s highly contaminated.

Now we’re entering the village of Paguate. People here are very sick. They’re suffering and dying. The majority of our people were working at the mines. From January 1, 1972, the uranium mining industry just expanded so much, and everybody was employed there at that point. I was living in Seama Village. I live about 11 miles from the mines, down in the valley. I’m in the farthest village, actually. We have six villages in Laguna Pueblo.

We arrived at Chino’s house. In her living room, she read from a poster she’d made.

Chino: These are recollections of my childhood memories, and I’ve titled it, “Memories That Do Not Heal.” The recollections of childhood memories living in Paguate village are of pain, heartbreak and anger. Anger. Uranium mining operations began near our village in the 1950s. A frightening sound became an everyday event. A dynamite blasting happened at least twice per day. When the blasting occurred, everything vibrated. The village shook. The houses built with rock and mud were affected by the vibrations. The pictures that hung on the walls fell.

As children, we were so curious and excited by the loud explosive booms coming from the uranium mine. We figured out the blasting schedule. We gathered at the edge of the village to observe the huge billowing of dust clouds after the blast. The clouds of dust drifted over the village and settled on everything. Women dried fruit and meat outside their homes. Families ate the contaminated food, not knowing the eventual consequences. Years passed. The continued blasting caused cracks in the walls of homes. The outdoor oven walls cracked. The women could not bake bread, roast corn or cook. Today, there are no ovens to be used as they once were. They are in disrepair. As mining operations continued, miners and community members were exposed to the toxic environment.

The Jackpile Mine closed in 1982. Since then, we’ve lived with the knowledge that many community members are sick and dying from cancers. Kidney and respiratory diseases. My beloved spouse, a Vietnam veteran, parents and other relatives passed away from the uranium diseases. These are memories of my childhood growing up in the village so near to the uranium mine.

Anderson: Once you disrupt uranium — and the government knew this — you can’t do anything to stop it from contaminating people. You just open up a porthole of illnesses and diseases. And that’s what our people are suffering from right now. They don’t know how to stop the contamination. There’s nothing they can do. It’s awful. It’s headed down the Rio San Jose, which is going toward Albuquerque and Las Lunas and Belen. And they can’t stop it.

They only have given us until 2027 to file RECA claims. That’s not enough time. Right now, I’m working with over 500 living miners, trying to get them going. We have all these attorneys and home health care groups that are causing so much havoc throughout the community. I told people: Don’t answer them. Do not give out your information. The city of Grants right now is just craziness.

We had a meeting recently and went through everything — and we told everybody to hold off. Our people are calling me asking how to apply, and to get tested, but right now the Radiation Exposure Screening and Education Program at the University of New Mexico is just swamped, because so many people are trying to get tested. I’m telling everyone to get a disc and a radiology report from their doctor, and then we can have the pulmonologist from RESEP read it, so he can do a B-read, in which a diagnosis is made from looking at an X-ray, to determine if miners qualify for compensation.

We left Chino’s house and drove toward the mines. We parked by the side of the road, near a tall wooden structure. Anderson warned me to look for snakes as I stepped over volcanic rock to walk to where Rodriguez stood, beneath the platform.

Vincent Rodriguez: The underground mine went almost all the way to the village. And it spread out like a spider’s legs. These motors were funneling cool, breathable air for the miners. Underground was very toxic with dust. They had to run the motors 24-7 because you had miners working 24-7. They did dynamite down there, with earth that contained uranium falling from the ceiling. They lined it with real heavy chain-link fencing. They put it up there to catch anything coming down. The fencing couldn’t catch all of it. Miners got killed. One story goes that they had taken a shortcut to their main drilling at Jackpile Mine. And they were crushed below ground while I was working on the surface. So there were a few fatalities in the underground area.

Rodriguez pointed toward the tiered cliffs that are gray with uranium from above-ground mining.

Rodriguez: As you can see, this was all open pit. It was blasting. The village had underground water springs, water tables, natural springs that kept the water coming out. The vibration from the blasting disrupted the fissures underground where the water table was, and that’s how a lot of the water got contaminated with the low-grade and high-grade ore.

We drove on, down a road that had been neglected since the mines closed in ’82.

Anderson: When it rains, there’s a metallic smell. It’s awful. When I drive, I’ll just cry. I think: Oh, my God, people are breathing this stuff and you can’t get it out of your mouth. We’d drive down into the mines, into the pit to pick my husband up and drop him off. I’d be with my kids; we’d have our windows open. Nobody ever told us it was dangerous.

We passed various vacated gray metal buildings beside a road that swooped down into the mines.

Anderson: All this is just waste. It was not high-grade ore. It was low-grade. It wasn’t high-grade enough to be used. This is all abandoned. This area here was the shop. They say that the people who worked at the shop aren’t eligible for compensation because they weren’t in the mines. But the shop people would go down into the mines. If a truck broke down, they’d be right in that dust, too.

The road circled around the mines and back up to the village, which looks over the gray cliffs. Many of the adobe homes are uninhabitable.

Chino: These are the older homes that were destroyed by the impact of the blasting. During the summer months, the ladies would re-plaster their homes. That was a fun time, because we got to play in the mud. See the oven to your right? That’s one of the ovens that’s no longer used. I wish they would cover it.

We parked at the edge of the village, less than a mile away.

Rodriguez: This is where they used to have their sheep, cattle and horses. That’s where I used to live with my aunt and uncle. The pig pen was over there. But that was before the mining. This was all barn area. And they used to plant corn or squash in this area right here. That all stopped when the mining industry started. Farmers became miners.

Anderson: Look where the winds are coming from. Right in front of you. This way. The silica, the dust that they blasted, is what scars the people’s lungs. Many of our Navajo brothers and sisters live close to contaminated mines, just like us.

The mining really disrupted life in Paguate. All my grandpas worked here when it started in 1952. When I started working in 2014, some of our older miners brought me their pay stubs. They were making like $1.80 an hour. To them, that was a lot of money back in the ’50s. That was nothing.

Paguate used to be beautiful. It used to look like that hill there, where all the cedar trees are. It’s so upsetting. Every time I talk about it, I get angry. Especially with me being an advocate, I get calls every week: Somebody passed away. Cancer. These horrible diseases that are not even qualified diseases for RECA compensation. We’ve had a lot of our young people die of cancer. They’re in their twenties and thirties.

Chino: It’s so unfair the way the government has specific health issues and only those can be compensated. It should be the whole body. Radiation doesn’t stop at your lungs. It’s everywhere. And that’s why I don’t understand why they list these specific illnesses. If you’re sick in your body, well, that’s from the radiation, I believe.

Anderson: Some of our young people don’t even know about the mining. They don’t even see it. Millie taught it in school. But that’s so many years ago.

When I was a child, it didn’t mean anything to me. And for some of our elders, it still doesn’t mean anything, because they don’t understand radiation and what uranium can do. That’s why I think our people have been so complacent about it. I mean, it’s like there’s no urgency.

When our coalition was fundraising in 2024 to go back to Washington, D.C., to lobby and protest, it was difficult getting people to donate. We did it on our own with food sales. We would sell burgers or Indian tacos or anything we could, just to raise money. It would take us maybe three weeks. It was a lot of work.

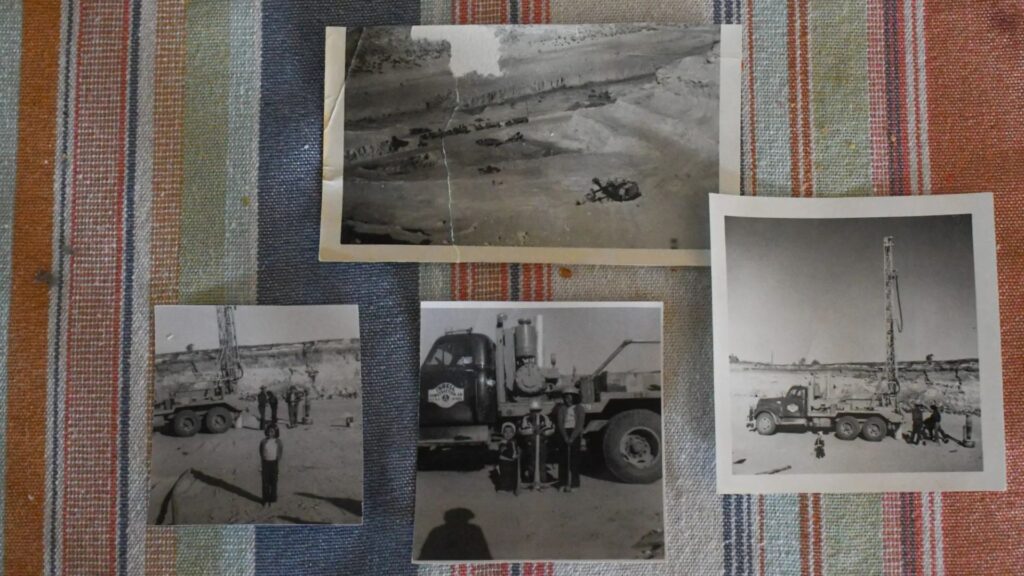

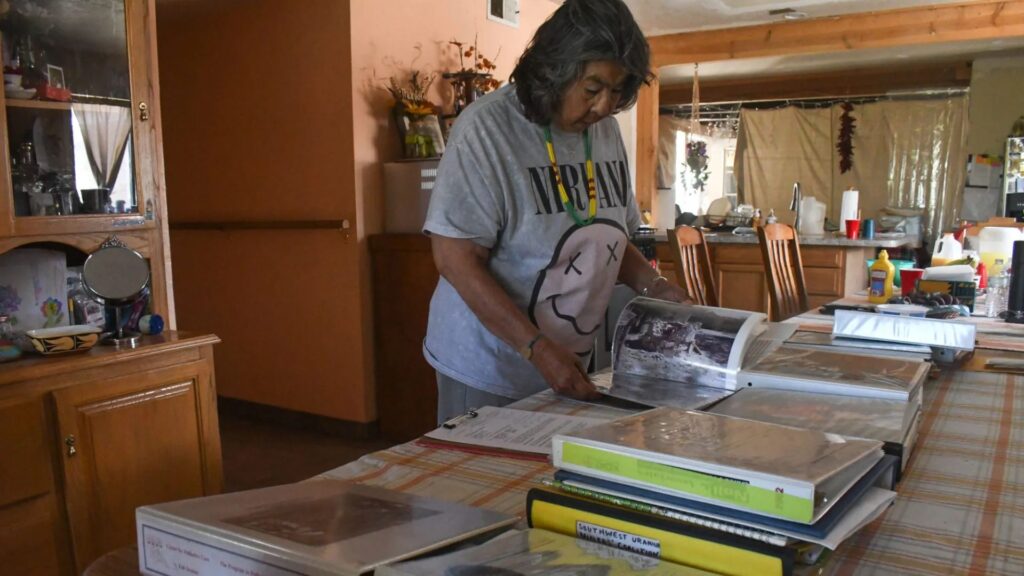

Anderson left for a meeting. Chino, Rodriguez and I went back to Chino’s house for lunch. We looked at old photographs at the kitchen table.

Chino: My husband was a miner after 1971. He had nine months over there, but the RECA criteria — before it was expanded — was that you had to have one year of working in the mines before 1971.

Toward the end of his life, some medical hygienist determined that he had low levels of exposure. I don’t understand that. That’s what makes me angry. Through 2023, he was back and forth with a lawyer, and every time a letter came in, he was hopeful. But then: “Sorry, you’re denied for RECA compensation” again. He said, “Why? Don’t they know the conditions we worked in?”

I got a letter because of James. But he’s gone, so I just filed it. It was from one of the home healthcare people in Grants. It says if he needed help, to contact them, and they gave a number.

The lawyers were rich from the people they represented to get money, compensation. So this time around, we’re just letting people know: Don’t say anything to any lawyers. Right now, meetings are important, but only if you give out the right information.

Rodriguez: In ’82, during the Reagan administration, when the warehouse in the mine where I was working got word that the mining was going to be shut down, it was because the ore was being processed and mined out of the country. I heard it was China. Lower price. We had just gotten through with going on strike for higher wages — in 1979, I think it was. We went for higher wages all across the mining industry.

We got what we wanted. And then they shut it down. The mining went on over there on the other side of Grants for another, gosh, another six months. It didn’t shut down all of a sudden. The mining here, the open pit, it shut down. The company shut down the heavy equipment, the shovels, all the graders, they took them out of the pit. They just left them there until they loaded them up for auction to send off to someplace else, or just to scrap them.

After the mine shut down, I know many people went off to Albuquerque and Grants. Some were commuting. I did odd jobs after the mines closed. If the mines were still going, I would have been still in bed and just be happy and retired.

Chino: No one has ever really mentioned the destruction to our cultural way of life. Using our ovens, going rabbit hunting. That’s all gone. Everything that we did is gone. As a kid, I remember there were events where the people spoke only our language — Keres. So now that those are gone, you don’t hear it anymore. That’s why we’ve lost a lot of our own language. Vincent remembers that, on Saturdays, there would be the Saturday bake. And that’s when the mothers and grandmas would make the bread for the week. You could smell the smoke coming through the way. And then the smell of the bread baking. And through the village, you could smell that smell everywhere.

One day I took my kids on a field trip, and this poor lady was standing there crying because that was the day they bulldozed her house. Because it was beyond repair. And she was crying. How would you feel? All the memories of everything. Growing up there, bringing children up in that house. And it’s gone. Well, she’s gone too, but her grandson has a trailer there.

One of my students came back to me. He said, “Mrs. Chino, I didn’t know my dad was a miner there, destroying the earth, destroying what we had.” Well, that was work there. Can’t blame him.

I need to find somebody who can fund my storybooks. I know what I grew up with, so that’s why I need to tell the story.

This story was originally published at Searchlight New Mexico, a NMPBS partner.