Fact-checking miracles: inside the multiyear effort to canonize Sister Blandina Segale

The Vatican may grant sainthood to a nun who knew Billy the Kid, tended the sick, taught children and advocated for immigrants. Making that happen requires a unique blend of faith and boots-on-the-ground dedication.

By Molly Montgomery, Searchlight New Mexico

This story was originally published at Searchlight New Mexico, a NMPBS partner.

There are lines in an old play that changed a woman in Albuquerque into a magician. Her name is Lisa Cousins. This was maybe 30 years ago. She loved to read, especially books about the spiritual realm, because when she’d given birth to her first child, the love she felt for him was so deep that she believed there must be more than the material world. In the first year of his life, she dreamt every night that she lost him. Then she’d find him again.

When he was ten, she read Percy Bysshe Shelley’s 1820 play “Prometheus Unbound,” which is about a network of mythological beings freeing a beloved son from a cruel punishment. It ends with a call to “hope till Hope creates/From its own wreck the thing it contemplates.”

Many times she read it. Her son, she recalls, was reading about Harry Houdini. She recognized the beauty of the play in Houdini, a being who could escape any confine. So she trained to be a magician: she learned to turn white silk into colored silk, and to make a watch vanish from one of her wrists and materialize on the other, and to make a woman appear in a box.

Twenty or so years passed. Then, Cousins believes, a Catholic nun named Sister Blandina Segale transformed her into a grandmother. Sister Blandina was born in 1850. She died in 1941. But her devotees believe that she listens from beyond the grave.

“Asked about the relevance of Blandina’s life to lives today, her champions often point to the global hostility and violence toward immigrants. Archbishop John Wester, head of the Archdiocese of Santa Fe, says that the care Blandina showed to people who’d recently arrived in the U.S “gives a model of what I believe our country should be, how the posture of our country should be toward immigrants.”

Cousins felt she’d lost her son, for reasons she doesn’t want to discuss. Conversation between them had become rare and difficult. She was living in Hollywood by then, performing at the Magic Castle, and he was living in Albuquerque with his partner and a child, a baby girl.

Nine months after the child’s birth, Cousins traveled to Albuquerque to see her. She couldn’t reach her son. Traipsing around Old Town, feeling “a loss of a whole part” of herself and a sense that her efforts in raising him had been “worthless,” her eyes fixed on the name of the gift shop for the San Felipe de Neri Parish: Sister Blandina Convent. More than a century ago, Blandina had lived and taught there.

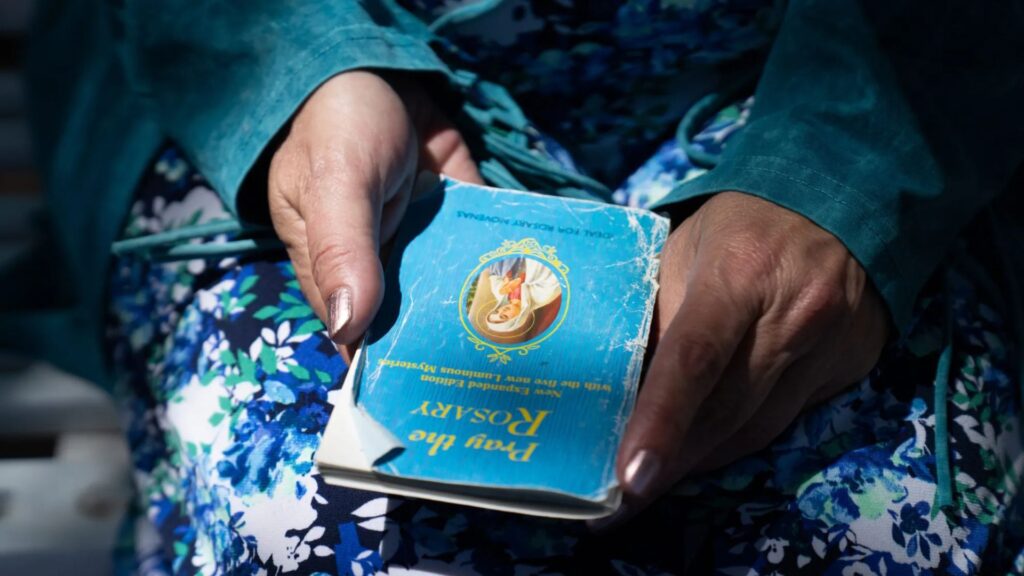

Cousins wasn’t Catholic, but she wandered into the gift shop and bought a one-dollar booklet titled “How to Pray the Rosary.” On a sidewalk bench, she opened it. At that instant, she got a text from her granddaughter’s mother, asking if she’d like to see her granddaughter.

The date, September 21, was the same day that Blandina, many years ago, opened the first public school in Albuquerque, according to a plaque on the building. “It was the start of my education,” Cousins says. “She was still teaching.”

“This Journal which I propose keeping for you”

Go back about 150 years and north about 250 miles. One night in December, on the plains of southeastern Colorado, a 22-year-old Blandina sat in a stagecoach with what she would later describe in a journal entry as “a lonely, fearful feeling.” She’d left her siblings and parents in Ohio. She’d been missioned to a Colorado town called Trinidad, which she’d pictured as a community on the island of Cuba.

The darkness drowned the grasses and clotted into the Sangre de Cristo Mountains ahead. At the eastern edge of the mountains lay the town. A few more hours in the stagecoach, jolting and shuddering over packed earth, and she would arrive.

The driver stopped for supper, but the night scared Blandina so much that she couldn’t eat. In Ohio, some men had told her that “no virtuous woman is safe near a cowboy.” Now cowboys were “constantly” on her mind. Around midnight she heard footsteps. A “tall, lanky, hoosier-like man” clambered into the carriage beside her, she wrote. “By descriptions I had read, I knew he was a cowboy!”

Without asking permission, he draped over her a buffalo hide that he called, in a Western twang, his “kiver.” Beneath the kiver, she thought of God. Then — and it’s not entirely clear why she did what she did next; maybe she was surrendering to God’s will — she shifted her body so that the cowboy could more easily shoot her through the heart.

“I expected he would speak — I answer — he fire,” she wrote. “The agony endured cannot be written. The silence and suspense unimaginable.”

But instead of a gunshot she heard questions. “What kind of a lady be you?” he asked. She said she was a Sister of Charity. He wanted to know whose sister she was, and if she was “Quaker like.” She wanted to know why he became a cowboy. He said he’d read about them and run away from home. She asked if he’d written to his mother. “No, madam,” he said, “and I allow that’s beastly.” She told him to write to her as soon as he got off the stagecoach. “I will, so help me God!” he said.

A few years after Blandina took up her calling in Trinidad, she was missioned to Santa Fe, and then to Albuquerque. (Later, she would return to Ohio.) During many of her years in the Southwest — 22 in all — she wrote journal entries for her biological sister and fellow nun, Justina, who was assigned to various locations around the Ohio Valley. Blandina called Justina her “dearest dear” and told her about amazing things she’d done out West: saving a man from a lynch mob; befriending outlaws like Billy the Kid and trying to steer them away from violence; motivating townspeople to build schools, where she taught.

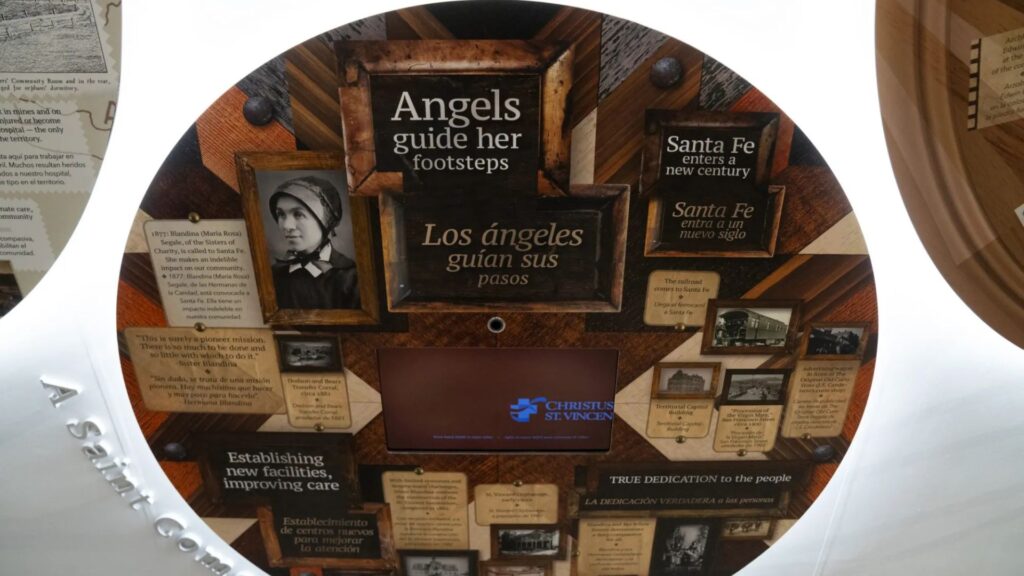

In Santa Fe, she lobbied the legislature to fund one of the first public schools in the state and spent a good deal of time tending the sick at St. Vincent Hospital, which nuns from her order had established a decade earlier. At one point, a Santa Fe county commissioner refused to pay for patient burials; Blandina made sure he’d pay by threatening to deliver a corpse to his office. Another time, the roof of the hospital caught fire, and Blandina climbed a drainpipe so fast that men watching from the ground believed she had levitated. “I marvel how composedly I acted,” she wrote to Justina, adding a little later: “I doubt not the men think I’m either a saint or a witch.”

In 1932, by which time Justina had died and Blandina had turned 82, she published the journal as a book called “At the End of the Santa Fe Trail.” Who knows why one narrative takes hold and another slips into oblivion, but Blandina’s stories captivated people. In the decades that followed, she appeared in comic books and on television, cast as an innocent nun venturing out to the Wild West.

A friendship between a nun as pure as Blandina and an outlaw as sinful as Billy the Kid seems an unlikely thing, an angel talking to a demon. Other writers seized on those sorts of details and spun them into narratives that accorded with colonial ideas so fundamental to U.S. culture that they still often go unquestioned: that the West was a place in need of civilizing, and that the Catholic church could be a civilizing force.

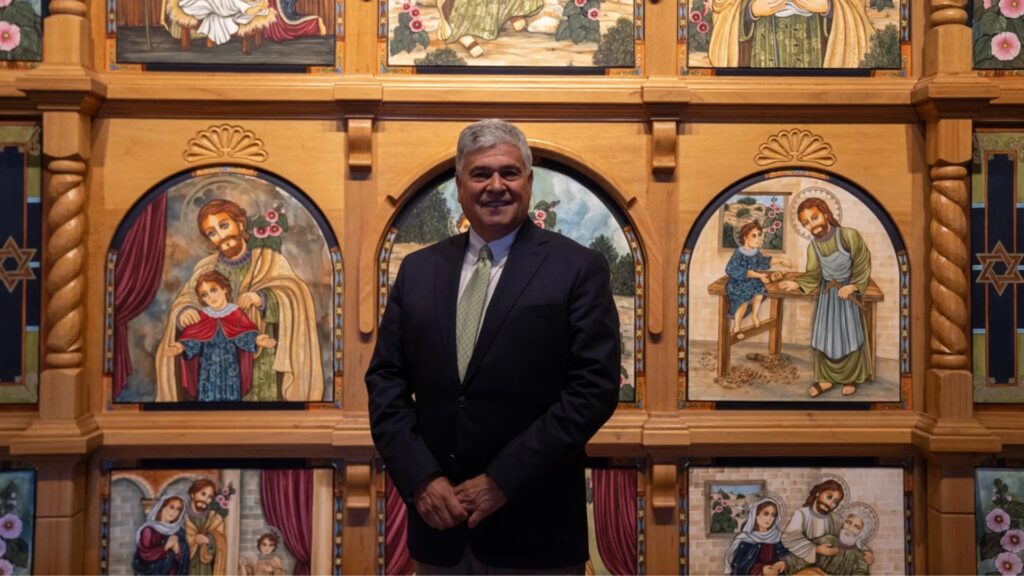

Blandina’s notoriety persisted into the 21st century. In the early 2000s, a man named Allen Sánchez — the president of an Albuquerque-based community health organization that Blandina founded — prayed with her in mind. The prayers and the journal guided him during a transition that the organization, CommonSpirit St. Joseph’s Children, was weathering at the time. It endured, and Sánchez began to think Blandina might be a saint.

Backed by the CommonSpirit St. Joseph’s Children board, he took the idea of canonization to Michael Sheehan, who was then Archbishop of Santa Fe. Eventually, the Archdiocese opened an investigation as part of a “cause” — a complicated, multi-step process, often spanning many years, in which a council at the Vatican scrutinizes the deeds a person performed in life and the miracles attributed to them in death, to determine whether they qualify as a saint. This marked the first time that a New Mexican diocese had asked the Vatican to examine a candidate for canonization.

As word spread about the investigation, more and more people began talking to Blandina while they prayed. Hundreds of nuns and thousands of parishioners, many in Colorado, Ohio, New Mexico and Italy, have prayed to her at least a few times. Devotees have now attributed 51 miracles to her.

But before all this fame, there was a journal that belonged only to two. In Blandina’s first entry, she told Justina that the account was a “Journal which I propose keeping for you.” She opened the published version with these words: “Into the keeping of this Journal of my Life in the Southwest, there never entered the thought of its publication. The reward for the work involved was to come if Sister Justina and myself would meet and read it together.”

It is a document of separation. Before Blandina went west, she had to say goodbye to her family for many years. She writes more than once that she managed not to cry. The repetition suggests that it took some effort.

The patron saint of immigrant children

Separation was not a new experience for Blandina. When she was four, she, her parents and three sisters left a northern Italian village called Cicagna. Their family had lived there, among fruit orchards, for generations. They crossed the ocean and landed in New Orleans and immediately encountered violence: The day they docked, a man hit Blandina’s father in the head, while another tried to kidnap her. She clung so tightly to her father’s hand that the man couldn’t pull them apart. She cried out in Genoese, and other immigrants overheard and stopped to help. The attackers fled.

The family split up for a few months so that Blandina’s father could look for housing in Cincinnati. (The reason he chose that city is unclear.) Blandina went north with him and prayed to be reunited with her mother and sisters. Eventually, the whole family reached Ohio and moved into a one-room apartment divided into four quarters by strips of calico hung from wires. Blandina’s sister Catalina, a young child, fell ill and died soon after.

Blandina’s early memories informed her work. She was often critical of the United States government for its treatment of non-citizens. In the 1890s, not long after she returned from the Southwest, she and Justina were reunited in Ohio, and together they went on to establish a settlement house and lead classes for immigrants, among other efforts. Blandina also worked to prevent human trafficking. If the Vatican canonizes her, she’ll be the patron saint of immigrant children.

It’s not unusual for the Vatican to saint someone whose life is in some way relevant to a contemporary issue. A popular figure soon to be canonized, Carlo Acutis, was a technologically savvy Milanese millennial. In life he built a website listing miracles, and in death he is said to have cured a boy of a pancreatic defect and a woman of a brain hemorrhage.

“Canonization is always about holiness, but it’s never only about holiness,” says Kathleen Sprows Cummings, a professor of American Studies at Notre Dame. “It’s about what need that saint, and the saint’s story, fulfills for the church at any given moment in time and in any given place. To my mind, it doesn’t detract from a person’s holiness at all to acknowledge that.”

Asked about the relevance of Blandina’s life to lives today, her champions often point to the global hostility and violence toward immigrants. Archbishop John Wester, head of the Archdiocese of Santa Fe, says that the care Blandina showed to people who’d recently arrived in the U.S “gives a model of what I believe our country should be, how the posture of our country should be toward immigrants.” Wester says she also stands as a counterexample to sexist stereotypes — through her courage, stamina, toughness and practicality.

Blandina’s cause may have the indirect effect of mitigating problems within the Church as well. Alongside dozens of dioceses across the country, the Archdiocese of Santa Fe declared bankruptcy in 2018, as part of a process of settling lawsuits with people who’d been sexually abused by priests, usually as children. The cause, Wester says, is “a reminder that the church is infinitely bigger than a bankruptcy or sex abuse scandals, which the church must continue to reckon with.” After the bankruptcy, Wester asked worshippers to pray to Blandina, along with St. Francis and Our Lady of Guadalupe.

But the coincidence of the cause and the bankruptcy is just that, Wester says. “We didn’t say, ‘Oh, dear, we’re having all these troubles. Let’s see if we can make a saint.’” He points out that the cause opened years before the bankruptcy, and that it was initially supposed to be overseen by the Archbishop of Cincinnati. It was transferred to Santa Fe because of the time Blandina spent in New Mexico.

Allen Sánchez says that it’s God who decides when a cause will open, for reasons that may or may not obviously tie in with contemporary issues. He had the idea to petition for Blandina’s cause because she emboldened him during a difficult time.

CommonSpirit St. Joseph’s Children opened as a hospital at the beginning of the 20th century; at the beginning of the 21st, it became a community health organization focused on early childhood services. As board members navigated the transition, Sánchez says, they found “consolation” in Blandina’s stories and began to discuss the possibility of asking the church to look into her deeds. But they didn’t take any action.

Then, in 2013, Sánchez learned that there were three nuns, ages 98, 100 and 101, who had memories of spending time with Blandina. They were the only people who could provide testimony about working alongside her. If the board of CommonSpirit St. Joseph’s Children waited any longer to petition for the cause, Sánchez worried, investigators might lose the opportunity to interview the nuns. So they voted unanimously to sponsor the effort.

“Whatever is happening in society today, it’s a different deal,” Sánchez says. “Eleven years ago, we weren’t having mass deportations. But her story fits the time. That’s how God works.”

“Pomp and ceremony”

Sánchez — a leader in the effort to repeal the death penalty in New Mexico and a member of the State Investment Council — is also an advocate for immigrants’ rights. At a rally in February, he stood on a stage beside the New Mexico Roundhouse. Before a cheering crowd, he addressed President Trump. “Mr. Trump! Mr. Trump! Jesus was an immigrant!” he shouted. “I forgive you! But you gotta change! You gotta change your mind! You gotta change your heart!”

Blandina has inspired much of Sánchez’s recent work. He spent a decade lobbying the state legislature to appropriate funds for early childhood education and believes that she was there with him, since she had lobbied for education herself. In 2022, New Mexico became the first state in the nation to guarantee early childhood education as a constitutional right.

Secular publications have often described petitioning for sainthood as lobbying. Sánchez says it’s more like a court case. But the persistence he displayed in the legislature should serve him well in Blandina’s cause: the process can span decades, sometimes centuries.

Church officials look for extensive proof that a person is, in fact, holy, in the ways they’re hoping to promote. The proof required is twofold: petitioners must show that the candidate lived a heroic life; they must also show that the person is in Heaven, talking to God. Miracles, which usually take the form of physical healings that can’t be explained through worldly causes, demonstrate that this conversation is happening: It is God who performs them, but it is the saints who intercede between Him and the people on Earth who pray for help. If a miracle happens right after someone spoke to a saint in prayer, it means the saint had God’s ear.

Gathering evidence can be extremely time-consuming and expensive, involving, among others, a petitioner, who asks the church to open a cause; archivists and investigators, who research a candidate’s life; doctors, who testify that there’s no medical explanation for reported healings; and postulators, often compared to lawyers, who argue the candidate’s cause before a council at the Vatican. Some modern groups have paid more than half a million dollars to support causes.

Historically, the process has often been riddled with corruption, with funds disappearing into the coffers of the postulators. Pope Francis worked to implement greater transparency, and Pope Leo XIV has positioned himself to continue that effort. Experts note that wealth doesn’t guarantee sainthood, but the fact remains that it’s very difficult to petition for sainthood without money.

“You need some money, because you need to compensate people for their labor,” says Professor Cummings, who also compares the process to a court case. “If you want to bring a suit against somebody, you need to hire a lawyer. And then, if you want to appeal the decision, you need to hire more lawyers.”

Over the past decade, Sánchez talked to priests and a private investigator, doctors, the elderly nuns who knew Blandina, people recovering from illness and people turning to her in despair. Researchers gathered 14,000 pages of evidence about her deeds and miracles and sent them to Rome, translators translated correspondence written in English, Italian and Latin and a postulator arranged the documents into an 800-page testament to her saintliness.

In June 2024, nine historians at the Vatican approved the account, meaning that there is now a possibility that the Pope will recognize Blandina’s heroic virtue by announcing that she’s Venerable. If people can prove that a miracle is attributable to her, the Pope may declare her Blessed; if a second miracle occurs after this declaration, she may become Saint Blandina.

So far, CommonSpirit St. Joseph’s Children, which has a trust fund of over $100 million, has spent $83,017.85 on the required costs of the cause — mostly covering printing and the salaries of postulators, researchers and translators.

Sánchez says that CommonSpirit St. Joseph’s Children has spent more than $85 million on early childhood services and argues that the expenses of Blandina’s cause are well worth it. “If this inspires immigrant children, then it’s worth every penny,” he says. “There might be people who object to spending money on this instead of feeding families. We’re creating the good will that will feed more families.”

Some of those who love Blandina don’t care whether she is officially recognized. Sister Kathryn Ann Connelly, a Sister of Charity in her nineties, says she’s run into several people who pray to Blandina but aren’t concerned with the Vatican’s procedures.

“There are lots of people that don’t go for the pomp and ceremony, and they don’t go for the amount of money that it takes to go through this process,” she says. “There are people who are being hurt by the church, and some are being driven away. They’re finding God someplace else. And they’re not happy with that, they’re sad about it, but that’s the way it is.”

“The correct spirit of Catholicity”

Blandina arrived in New Mexico as the U.S. was colonizing the territory. Those who honor the priests and nuns who traveled here often point to their work building hospitals and schools. There’s also a more painful history.

The Spanish had colonized New Mexico long before; Catholic leaders were active and often violent participants in that conquest. But many of the descendants of Spanish and Indigenous people modified Catholic traditions and integrated them into their lives. After 1848, as the U.S. government took over the territory, those practices became subject to colonization. The Archbishop of Santa Fe, Jean-Baptiste Lamy, a Frenchman who came to New Mexico by way of Cincinnati in 1851, denounced New Mexicans’ traditions and tried to force New Mexican Catholicism into a European mold.

“When he comes here, he looks at us as very low-class people,” says Robert Martínez, New Mexico’s State Historian. “We have our penitentes, which he’s shocked by. We have our santos; he thinks they’re ugly, that our adobe churches are ugly. He thinks the local priests like Padre Martínez or other priests with names like Gallegos and Ortiz are immoral, insufficiently Catholic, and he feels that it’s his mission and duty to re-Catholicize us.”

Lamy hired French architects and Italian stonemasons to construct a Romanesque cathedral around the adobe cathedral near the Santa Fe Plaza. Workers carried the old cathedral out in pieces through the new front doors. He declared that spires should be erected atop the flat roofs of other adobe churches. “That’s a metaphor,” Martínez says. “He was putting those on top, trying to make them look more European and less New Mexican, less Puebloan, less Mexican.”

Lamy also directed members of various Catholic orders to come to the territory. “Native Americans and Hispanics are savage and inhuman, and anyone who comes here to somehow improve us, save us, that’s beatitude,” says Hilario Romero, a former State Historian, who has discovered, through oral history, sexual abuse of New Mexican children by the Jesuit priests Lamy oversaw.

Another order who came at the behest of Lamy was the Sisters of Charity, Blandina among them. She adored Lamy. She called him “beloved” and a “hero” of the church. Like him, she criticized the penitentes, writing to Justina that they possessed “not the least conception of the correct spirit of Catholocity.” She later wrote that “the Indian possesses the vices of barbarism, but he also possesses a nobleness of character, by which, with just treatment, religion and civilization, he can attain to the ideal man.”

Although Blandina could be blind to the church’s colonialist tendencies, she was critical of colonialism elsewhere. She defended Indigenous people’s land rights and railed against the U.S. government for its betrayal of treaties and agreements, as well as for its genocidal campaigns. She condemned the way U.S. “land grabbers” were displacing Mexican people.

How these conflicting tendencies affected her relationships with people in New Mexico isn’t entirely clear, though I couldn’t find evidence that anyone had issues with her. Gov. Richard Dillon, who led the state from 1927 to 1931, encouraged Blandina to publish her journal and praised her “heroic achievements.” Albert Daeger, a former archbishop of Santa Fe, wrote in a 1930 letter that “Sister Blandina is still remembered by many of the ‘old timers’ out here, and they know that what she says or writes is the truth.”

Nor did I find anyone who seriously opposes the canonization effort. Romero says he doesn’t believe Blandina deserves to be a saint, because some of the attention surrounding her comes from her unexpected connection to Billy the Kid. He notes that another nun who worked in New Mexico around the same time, Katharine Drexel, has already been sainted. He thinks, however, that Blandina should be honored for her work founding schools.

Martínez says Blandina set “an excellent example” for Christians and non-Christians alike. Canonization “doesn’t mean Sister Blandina was perfect,” he says. “It means that when she fell short of that Christian and Catholic ideal, she got back up and kept going.”

“To be loved”

As part of the effort to prove that Blandina lived a heroic life, former Archbishop Sheehan appointed a private investigator named Peso Chavez to look into her autobiographical accounts. Based in Santa Fe, Chavez has been investigating all kinds of people for more than half a century. He worked as a public defender before turning to the private sector, and has researched issues ranging from homicides to civil lawsuits to death penalty cases. What he has repeatedly learned, he says, is that “we all want to be loved, and we all want to love.”

Chavez recalls Allen Sánchez saying to him, “Peso, go out and find whatever you can, good, bad or indifferent.” Chavez describes the freedom he felt as “just beautiful.” In previous cases, he’d sometimes researched old events, from maybe 30 years ago. He was following Blandina 140 years into the past. He began with her journal.

The journal is full of fantastic images that are difficult to verify. A tall outlaw in velvet rides a “spirited animal of unusually large proportions.” A woman Blandina describes as a “huddled dressed-up skeleton” with a terrified expression crouches in a corner, begging for a place to die. A patient on the roof of St. Vincent Hospital “dances to the moon.” Blandina is momentarily struck blind while carrying a coffin. She calls herself a “shrunken resurrection plant” — a ragged desert species that can survive without water for years. She describes insects that rain down from the ceiling of a dining room as “odoriferous acrobats” that have great “knowledge in mind reading.”

The journal also contains frequent descriptions of Blandina’s own heroism. In Trinidad, she reported that a mob was clamoring to hang a man who’d shot another. She encouraged the perpetrator to apologize and accompanied him past the mob to the bedside of the victim. The victim forgave him, and the men in the mob, who were craning their necks to listen to the interaction, allowed the shooter to live and stand trial in court.

Famously, she described three encounters with William Bonney, better known as Billy the Kid. She wrote that she first met him while tending to a dying friend of his. He told her he was planning to scalp four doctors who had refused to help his friend. She persuaded him not to. A couple of years later, she was traveling across the plains between Las Vegas, New Mexico, and Trinidad with some men who were greatly afraid of Billy. He was rumored to be near. If he was, she believed, he’d be carefully watching the plains. So she prayed the rosary on the open land at dusk to signal to him that she was among the travelers. When he passed them the next day, he waved his hat in the air and made his horse dance. She saw him a third time while visiting someone in the Santa Fe jail. His hands and feet were chained to the ground, and she lamented “the extreme discomfort of the position.”

Sánchez asked Chavez to research these stories with particular care. He sifted through old court records and newspaper articles and tried to imagine an earlier Southwest, a place of dirt roads and saloons that doubled as courtrooms. Using a court docket and a newspaper article, he was able to prove that the trial of the forgiven shooter did, indeed, take place.

Things got tangled when Chavez learned that several men referred to themselves as Billy the Kid in the late 1800s. Different historians have offered different accounts of where the real William Bonney was at any given time. “There were all kinds of Billy the Kids,” Chavez says.

But ultimately he found no reason to doubt Blandina’s descriptions. In two instances, it seemed plausible that Blandina and Bonney were in the same places at the same times. In a third, he found a courthouse record of Bonney being jailed around the time Blandina recalled visiting the jail.

Now and then, the dates and geographical locations Blandina recorded don’t make sense. But the discrepancies could be attributed to the fact that she compiled her book from various entries, decades after she wrote them, potentially editing errors into the text.

Regardless, her devotees tend to believe her wholeheartedly. Sánchez sees Blandina’s self-confidence as a kind of humility, a refusal to be false. “Part of humility is acknowledging your talents and acknowledging your abilities,” he says.

Reading the journal, I found myself thinking back to the note Blandina opens it with — how she kept it so that she and Justina could read it together. From 1873 to 1874, Blandina stopped keeping the journal, because, she said, “The things I could write are so ghastly that they had better be left untold.” Two years later, she wrote, “Dear Sister Justina, were I to write many of the incidents of daily occurrence, this journal kept for you instead of giving you a little diversion, and perhaps a wee bit of knowledge, might bring you only sadness and weariness.”

Justina’s presence made me recall the line in Shelley’s play that meant so much to Lisa Cousins: “to hope till Hope creates/From its own wreck the thing it contemplates.” Blandina’s hope to make Justina happy, and to be close to her, seemed to motivate the writing.

“I think the real holiness or specialness of the book,” Sánchez says, “is that you’re grasping what she’s intending for Justina.”

Lungs that were turning to stone

Since the nine Vatican historians have approved the account of Blandina’s heroic life, those arguing for her cause now must show that she’s in Heaven and can talk to God. The evidence will consist of miracles.

The miracles that the Vatican counts have to be inexplicable by worldly forces. They typically take the form of healings that doctors don’t understand. Religious officials and physicians hired to work on the cause interview other physicians about whether they know of anything that could explain the healings. Petitioners also have to demonstrate that it was Blandina alone who affected the miracles. The easiest way to do so is to show that those who prayed for them prayed to her alone and that the miracles occurred soon after the prayer.

In all, Sánchez says, of the 51 miracles attributed to Blandina, at least 45 involve physical healings, though not all happened immediately after people prayed to Blandina.

Because the miracles involve people’s medical histories, they’re protected by privacy laws and can’t be revealed to the public. Church officials know about them because the miracles’ recipients brought them to their attention.

Pam Kent, a hairdresser from Cincinnati, told me about one she received. In January 2014, Kent was having trouble breathing. Doctors told her it was probably asthma, maybe bronchitis. In April of that year, she says, “the air was just not there.” She couldn’t breathe well enough to get off the couch. Her fingers and lips turned purple. She was sent to the ICU and emerged ten days later with an oxygen tank and an order for bed rest.

A pulmonologist categorized the condition under the umbrella term “interstitial lung disease,” meaning that Kent’s lung tissue was thickening and hardening, though it wasn’t clear why. In her hair salons, she may have breathed chemicals from aerosol cans, which, the doctors speculated, could have caused the damage — though Kent doesn’t think so, since she was careful about cleaning the air with industrial purifiers, and none of the women she worked with got sick. She says that one pulmonologist used the words “broken glass” and “honeycombing” to describe what her lungs looked like on scans. He told her that the scarring was basically turning the tissue to stone.

By midsummer, on an X-ray, it appeared that the scarring was “working its way up the lungs.” Because the doctors didn’t understand what had caused the condition, Kent wasn’t a candidate for a lung transplant. The pulmonologist warned her that, within two years, her lungs would likely fill with fluid that would drown her. She watched three people die of the same disease.

Kent had gone to a high school in Cincinnati, where nuns from Blandina’s order taught. One of them, Sister Kathryn Ann Connelly, who’d been Kent’s principal and later a hair client, saw her in church when she was sick. The sister and other nuns, unbeknownst to Kent, decided to pray to Blandina every night at 6 p.m. for Kent’s healing.

By the winter of 2015, Kent could sit up without using her oxygen tank. By early 2016, she was weaning herself off of it. The scarring receded. She lived.

“It’s very hard for me to comprehend it,” she says. “Because why me?” If there’s any answer, she thinks it might have to do with how she listened to her clients while she cut their hair. She says she’d do anything for them, and they’d do anything for her. “I was their friend,” she says. “I was their confidante. I was their everything.”

The communion of saints

The sainthood process draws a line between what’s official and what isn’t, what counts and what doesn’t. As I talk to people about Blandina, the fabric of their relationships with her often seems woven from things that don’t count toward canonization — emotional coincidences that occur in daily life.

A woman named Faye Ramirez, a team leader at CommonSpirit St. Joseph’s Children, attributes to Blandina a coincidence that prevented a mother from being separated from her baby. The baby was in the hospital and required special formula. The mother told the medical staff she couldn’t afford it, which led to them call New Mexico’s Children, Youth and Families Department to alert them that she couldn’t adequately provide for the child.

Ramirez visited the mother, who asked for help. Then Ramirez returned to the CommonSpirit St. Joseph’s Children office, talking with coworkers about what she could do. She happened to glance down at a donation box. It contained the exact formula the mother needed. “Things happen, and really, there’s no answer,” Ramirez says. “So I always say, ‘It must have been Sister Blandina.’”

Undergirding the theology of sainthood are ideas about relationships. There’s a network of relationships between the living and the dead, called the communion of saints: the living pray for the dead so that God will move them from Purgatory to Heaven, and the dead in Heaven talk to God to help the living.

Archbishop Wester places importance on relationships when he’s discussing sin and grace. “Sin is what fragments,” he says. “You name any sin, and it breaks down relationships.” He gives examples: racism and other forms of bigotry, slavery, failing to acknowledge another’s dignity.

“And grace,” he says, “builds up relationships.”

Learning about canonization, I’m struck by various tensions: How Catholic hierarchies and institutional abuse have led to fragmentation and loneliness among devotees; how the ideas about the networks of living and dead have led to deep relationships. How a private series of letters from one sister to another became the grounds for a sainthood process that is making one of the sisters famous. How her notoriety has, in turn, generated new interpersonal connections.

More than a single miraculous physical cure, or a ceremony, what seems to draw worshippers to the church, and to hold them there, is the strange conversation of coincidence: people talking to each other across the borderline between west and east, life and death, one person and another.

After Lisa Cousins became a grandmother, she read Blandina’s journal and learned that Blandina, more than once, told young men to write to their mothers. She was received into the church, with St. Anne, the mother of Mary and the patron saint of grandmothers, as her patron saint. Cousins made an Instagram page called “Our Literate Lady” and posted images she found of Mary reading, often beside Anne. To be near her granddaughter, she decided to move back to Albuquerque, and two weeks after she arrived she found out that she would soon have a second granddaughter. She spends her spare time with the two of them.

None of her relatives or close friends are Catholic. It’s not unlike being the only spiritual, female magician. “I do have a certain loneliness,” she tells me. “It is a cynical world.” But she finds companionship among the writers she loves, “two thousand years of people,” and she prays in Latin to pray with the same words they used, and they form a convent in her mind. “Blandina,” she says, “is part of that convent.”

This story was originally published at Searchlight New Mexico, a NMPBS partner.