Back to the Bottle: Lawmakers renew alcohol tax push as deaths remain high

by Ted Alcorn, New Mexico In Depth

This story was originally published at New Mexico In Depth, a NMPBS partner.

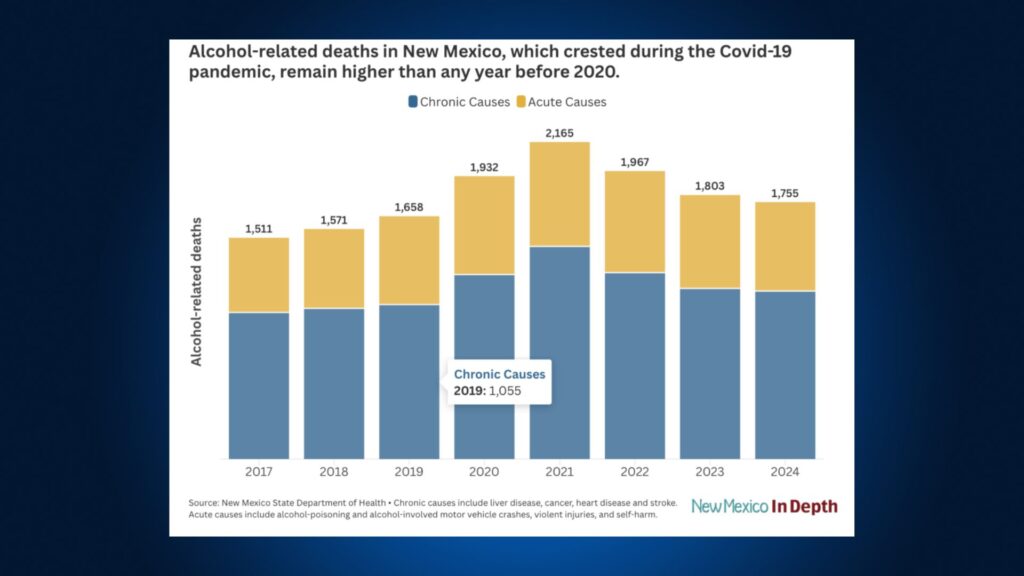

When the legislative session begins next week, Democratic lawmakers intend to revive a long-running effort to raise alcohol taxes as a means of reducing excessive drinking, which killed 1,755 New Mexicans in 2024, according to new Health Department estimates.

The latest proposal would create a new 3% sales tax on alcoholic beverages, according to one of the bill’s architects, Rep. Cristina Parajón, D-Albuquerque, while preserving the existing excise taxes that alcohol distributors are assessed based on the volume of alcohol they sell.

That is half the 6% levy Parajón and co-sponsors sought last session. “We think the proposal that we have this year is of the most reasonable,” she told the audience of a recent town hall meeting in Albuquerque.

For decades, excess drinking has been a top killer of working-age New Mexicans. In the latest estimates, a third of the deaths are attributable to acute causes like alcohol-fueled violence or vehicle crashes, and two-thirds are due to chronic causes such as liver disease and cancer.

New Mexico’s death rate declined 20% from a peak in 2021, according to the health department, but remains above pre-pandemic levels, underscoring an emergency which the state’s leaders have paid lip-service to but taken few steps to address.

Among the most effective ways of reducing demand for alcohol is increasing its price, according to public health experts, and raising alcohol taxes are the typical means of doing so. New Mexico’s existing alcohol taxes, which do not adjust for inflation, are at a 30-year low — between 4¢ and 7¢ per drink, depending on the type of beverage.

In each legislative session since 2022, lawmakers have introduced bills to lift those rates. Each time, even as they have broadened their coalition and moderated their request, they have fallen short. Time and again, a wide spectrum of businesses that sell alcohol — from brewers to wholesalers to restaurants and even gas stations — has fought off the measures.

In 2025, Parajón worked closely with Micaela Lara Cadena, D-Mesilla, vice chair of the House tax committee, but that is still where the bill died, after two Democrats voted against it.

The pair — Patricia Lundstrom, D-Gallup, and Doreen Gallegos, D-Las Cruces — both had ties to the alcohol industry and afterwards, Cadena took the unusual step of speaking out against what she perceived as her colleagues’ conflicts of interest.

During an interim committee hearing in October, Cadena seemed more determined, and said her duty as a lawmaker “is to our people, not to the alcohol lobbyist or industry or what they determine or decide.”

Lundstrom, on the other hand, remained unconvinced. McKinley County, which she represents and which has long struggled with high rates of alcohol dependency, is allowed to tax alcohol 5%, which she said was “a good thing.” But she was skeptical of imposing such measures statewide. “I’m not going to add more taxes on to McKinley County if I don’t see a clear path,” she said.

At last weekend’s town hall, when Parajón was asked whether the new bill had a better chance of passing the committee, she hedged. “I can’t really speak to how representatives are going to vote, especially when a new bill is brought forward.”

There is a precedent for adding a 3% sales tax: Maryland did exactly that 2011. In the years that followed, multiple studies found the change reduced alcohol–related harms.

At the town hall, another bill sponsor Sen. Antoinette Sedillo Lopez, D-Albuquerque, acknowledged the lawmakers had lowered their ambitions as they sought a bill they could pass. On a $2 beer at a convenience store, for example a 3% tax comes to little more than a nickel.

“How many of you would support paying five cents for a drink?” she asked the audience, who responded with a round of applause.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention long ranked New Mexico’s alcohol-related death rate the highest in the nation but it no longer does — because last year the Trump administration dissolved the agency’s alcohol unit, and disbanded its staff.

New Mexico Health Department communications coordinator David Barre said states were sharing data with each other to make such comparisons, “but it’s a work in progress.”

This story was originally published at New Mexico In Depth, a NMPBS partner.